On the road with the Mobile Medical Unit in Lebanon

For many people in Lebanon, mobile clinics are the only access to medical care.

“Eighteen, nineteen, twenty.” With nimble fingers, Lamise is checking the packages of medicines one last time before departure: painkillers, antihypertensives, anti-allergics, medicine for respiratory diseases and more. Enough medication for around 100 patients to last for almost three weeks. Last summer, at the height of Lebanonʼs economic crisis to date the local currency fell to a record low, and prices in the country skyrocketed. Even the most basic medication became unaffordable for most people in the country, and demand for economic assistance rose. “In July and August, our shelves were mostly empty,” Lamise reports. She nods towards her male colleague Sleiman, who cheerfully carries the large container from the storage room into the Mobile Medical Unit (MMU). This doctor’s practice on wheels is about to depart to treat patients in northeastern Lebanon, providing them with the most necessary medical care. For two days, I am invited to accompany this joint project between MI and the Order of Malta Lebanon as a journalist to learn more about their work and the most pressing issues around medical care in Lebanon.

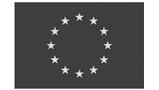

Four mobile clinics provide care in remote regions in North and South Lebanon

The MMU project was established as “mobile health for Syrian refugees and Lebanese affected by conflict” in 2015 and has then continued to expand since. Demand has only increased. Today, it includes a total of four mobile clinics, each located in the regions of Akkar (north), Baalbek-Hermel (northeast), Nabatieh, and Tyre (south). The Baalbek-Hermel MMU base is located in Ras Baalbek, in the Beqaa Valley about 120 kilometers from Beirut. Hemmed in by two snow-capped mountain ranges that separate the region from the Mediterranean coast to the west and Syria to the east, the Beqaa Valley runs through most of Lebanon. We are moving around the very north of the country, close to the Syrian border.

Many of the Lebanese who live here suffer from desperate poverty. In addition, the region hosts about 339,000 Syrian refugees, most of them in informal camps. Electricity from the state is only provided one to two hours at a maximum. Most people here can neither afford diesel for their private generators, nor the fuel to drive to a doctor’s practice or a hospital in the larger cities of Baalbek or Zahlé, some 40 kilometers away. The only medical care available for most comes from non-governmental organizations, such as the Mobile Medical Unit.

Our help in Lebanon

| 28,000 | people were served by the Mobile Medical Units in 2021 in the most remote regions of North and South Lebanon. |

| 40,000 | In addition to the mobile health care, MI supports the development of local health structures in a 4-year project. Part of the project is the modernization of eleven health centers and the establishment f a training center for medical staff in Beirut. Last year, nearly 40,000 patients could already be treated in the health centers supported by MI. |

| 9 | To improve the food situation in the country, agricultural actors in 9 locations are supported to be able to maintain production even during the crisis. |

First stop: Nabih Osmane

Today’s destination is Nabih Osmane, a predominantly Shiite village. Almost a third of its 8,000 inhabitants are refugees. This morning, thick fog lies over the fallow fields of the Beqaa Valley. Anwar, the driver of the mobile clinic, regularly has to dodge fist-deep potholes in the road. Winter has been particularly harsh this year. Storm Hiba paralyzed the entire region for two weeks in January, covering Lebanon with a thick layer of snow from 600 meters above sea level. The thermometers in Nabih Osmane showed minus seven degrees Celsius – a disaster for the refugees living in tents and the many Lebanese who are currently sitting in bitterly cold houses without electricity.

Today, as we reach Nabi Osmane, it is fortunately warmer, and even some rays of sunlight tentatively pierce the thick fog. It is the first time since the heavy winter storm that the mobile clinic stops here. In order to cover all villages and regions of the valley, the clinic uses a rotational system, visiting each location for one day at a time in a two-week cycle. During storm Hiba two weeks ago, only 41 patients made it to the clinic’s location in the center of the village, so this time demand is high. Many people are already waiting impatiently in the parking lot next to the local mosque where the 9-member team is setting up today. They have to provide care for at least a hundred patients today. Most of the patients coming today are of retirement age or families with children who cannot afford even the most basic medicines such as Vitamin D, Panadol, magnesium and calcium. At the mobile clinic, they receive basic health care and most medications they require. For specialized services and surgeries, patients are referred to primary health care facilities or hospitals free of charge.

Social worker Maysam is the first to jump out of the converted Nissan vehicle, which looks like a mix between an ambulance and a school bus. The young Lebanese woman is not letting the big crowd that is gathering around the bus break her composure: “One at a time, please take a number and wait for your turn.” She is supported by bus driver Anwar, and Touma, who drives the escort car. The two drivers distribute masks and disinfectants, take patient’s temperatures before they enter, and assign numbers to queueing newcomers.

Well-connected

In the mobile clinic, nurses Lamise and Sleiman treat the first patients together with pediatrician Dr. Hadi and field assistant Mariane. Field coordinator Elias, who heads the project in Baalbek-Hermel, kindly keeps the crowd in check and listens in on individual patients to see how they are doing. He is well-connected here and knows most people personally. Since he does this not only in Nabih Osmane, but in the entire region, his two phones never stop ringing.

Medicine for Ali

Elias introduces me to 14-year-old Ali Hassan and his mother Asmahan. They have been coming to the mobile clinic since the project began in Baalbek-Hermel two and a half years ago. Today, they came to have Ali‘s cold symptoms checked. He has the flu. But not only that: Ali has a mental disability and is hyperactive. He excitedly moves around the parking lot, barely staying in one place for a minute. Shyly, he shakes my hand to say hello but quickly turns away, clearly uncomfortable with strangers. Ali also suffers from diabetes and epileptic seizures.mHis mother, Asmahan, says that for over four months now he has been unable to get the medication he urgently needs. Because of his illnesses, Ali cannot attend a regular school. Until a few months ago, he went to a special center for children with disabilities, but due to rising prices, the family can no longer afford the tuition of 900,000 liras. By comparison, the legal minimum wage in Lebanon, which many nurses, teachers and public sector workers earn, is still around 675,000 liras. On this day, that only converts to about 33 USD a month. Thus, one month of education and care for Ali would cost his family a salary of one and a half months. “Since he doesn’t get his medicine anymore, he often gets sick and when he has a fever, he gets epileptic seizures more rapidly,” the mother reports. Now the shy boy with the friendly smile sits at home most of the time and gets bored. “He is often hyperactive, suddenly runs out into the street and between cars.

The neighbors usually have no understanding of people with disabilities and get annoyed by him,” Asmahan explains. “Then the whole neighborhood is in an uproar.” Because he is different, Ali is bullied by many kids in the neighborhood. On rare occasions, when he does get his medicine and calms down, he asks his mother: “Why am I different, mom?” Lebanese society is not yet ready for people like him, Asmahan says, barely able to suppress her tears.

But here at the mobile clinic, Ali is a boy like any other. While his mother describes his cold symptoms to the doctor and nurses, the boy scurries around the bus. Pediatrician Dr. Hadi though is not put off by this and manages to calm the boy with a few caring words and a firm handshake. Outside, field coordinator Elias takes Ali for a walk and even drives the boy home in the mobile clinic‘s escort car after the doctor’s visit. “I promised to drive him home if he behaves. And you must keep a promise,” Elias shouts out of the roaring car as he speeds over the parking lot.

Giving back to the community

In the mobile clinic, Mariane, the team’s field assistant, is examining 10-year-old Manal, daughter of a Syrian family in the Beqaa Valley that survives only from the support of non-governmental organizations. Manal has a lisp and needs speech therapy. “Unfortunately, we don‘t have time to give her therapy here. But I can refer her to a speech therapist for that,” Mariane says.

For Mariane, 23, working at the mobile clinic is her dream job. She is the newest member of the team and has only been there for just under six months. She is the only one among her fellow students who found a job just two months after graduation. Almost all her friends are currently unemployed; most of them are trying to leave Lebanon somehow. Not an option for Mariane: “Leaving my home, family and friends is not worth it to me.” The field assistant wants to continue working with children in Lebanon. Her dream: to open her own practice or even clinic here sometime in the future. “I see that there is a great need for this. I want to give back to my community.” Many of her friends have already left the country. Almost every household in Lebanon today has at least one empty bedroom where a brother, cousin, daughter, or grandchild once slept and who left the country in recent years for better opportunities. As this has been the case for many of Marian’s friends, these departures have left her with deep emotional wounds. “But fortunately, I have made new friends here at the mobile clinic,” she says, pointing at nurses Lamise and Sleiman. The team gets along so well that they even spend time together after work.

“We go hiking, camping and barbecuing together; we’re like family. It feels like we’ve known each other for ten years, not just five months.” The fact that the work in the MMU creates strong bonds between the team comes as no surprise to me. Every day, the group cares for more than 100 patients in a very confined practice. An enormous achievement.

Tensions never quite disappear

In the afternoon, the team drives back to the base in Ras Baalbek. The sunset tints the Beqaa Valley in deep orange. Before closing time, the team cleans the mobile clinic, checks the medical equipment and reorders medication. Tomorrow morning, the journey continues. Just seven kilometers to the south is the predominantly Christian village of Fakeha. The tensions between Christians and Muslims, Lebanese and Syrians have never completely disappeared since the civil war in Lebanon. It is within this complicated social fabric that the mobile clinic team moves day by day. “We are aware of it, of course, but none of that affects us in our daily lives,” Elias says. “What matters to us is that everyone here gets the same good care. That’s why the people come to us.”

And so, the mobile clinic rolls out again the next morning. One of the few visible differences between Fakeha and Nabih Osmane is the church that is standing in the center of town, instead of a mosque. The elderly ladies who line up here for their medicine and check-up do not wear headscarves, but crosses around their necks. But their problems here are the exact same: poverty, no electricity, and practically no medical care. I am learning today that despite everything, everyone in the Beqaa still says “Alhamdulillah” (in English: “Thank God”) despite the crisis – whether they are Christians, Muslims, Syrians or Lebanese.

Mobile aid worldwide

| In the Democratic Republic of Congo and Colombia, we also use mobile units to bring medical aid to people in remote, hard-to reach regions. |

| In Myanmar, India (as part of our COVID-19 aid) and Bangladesh, mobile teams visit patients at home, providing medical advice and health prevention. |

| After the outbreak of war in Ukraine, a mobile medical unit supported the care of refugees at the Ukrainian border. |

Text und photography: Tobias Schreiner